Prediction Markets: Gambling or Forecasting Tools?

Prediction markets sit at the intersection of finance, statistics, and human behavior.

They allow people to buy and sell contracts tied to future events, elections, economic data, wars, weather with prices, that reflect crowd-assigned probabilities.

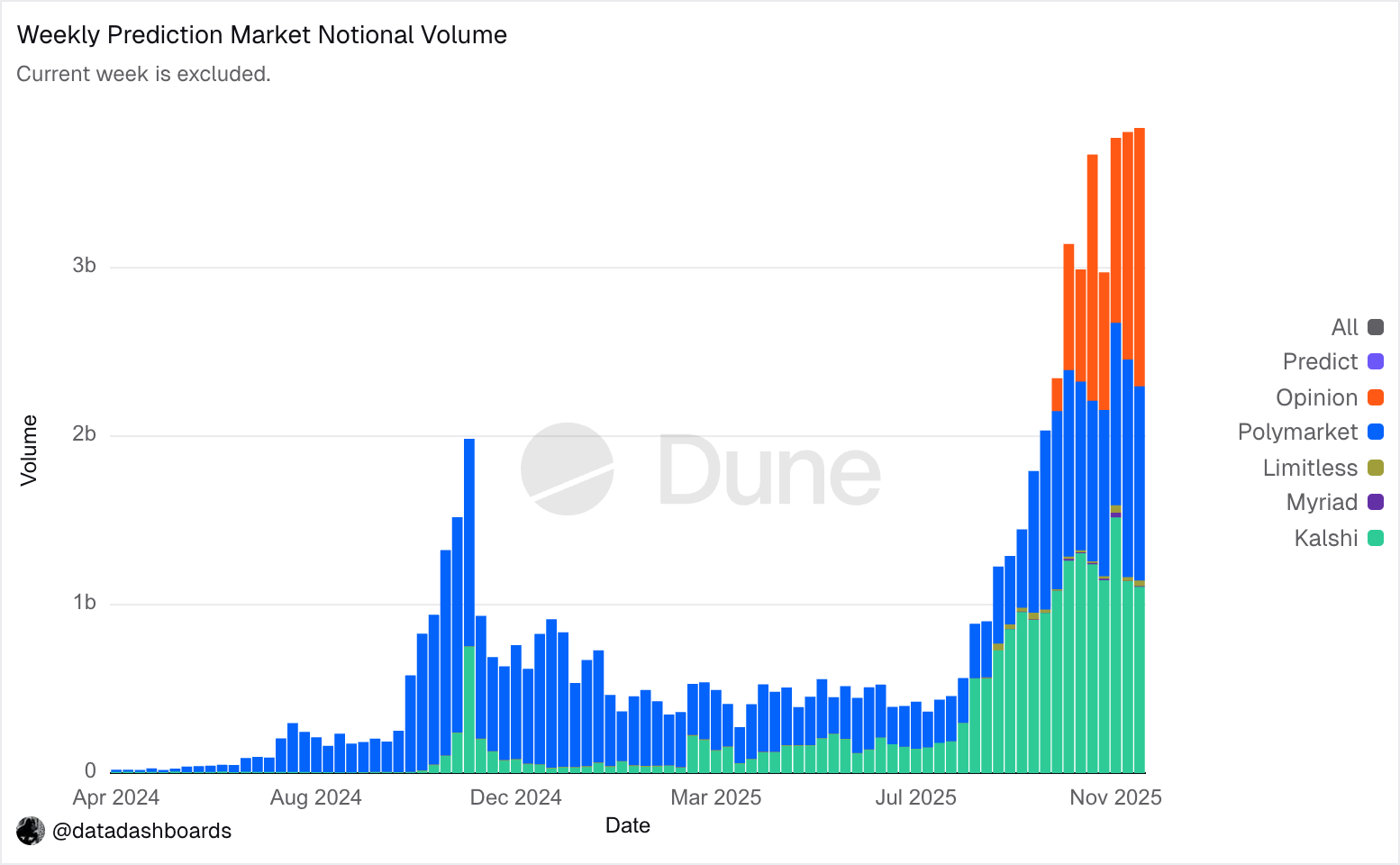

Platforms like Kalshi, which operates under U.S. regulation, and Polymarket, which runs globally on crypto rails, represent two very different visions of what prediction markets are and what they should be.

Whether these markets are best understood as gambling or as forecasting tools depends less on their mechanics and more on how they’re used, who participates, and how they’re governed.

How Prediction Markets Work in Practice

A prediction market contract typically pays $1 if an event occurs and $0 if it does not. If a contract trades at $0.65, the market is implicitly saying there’s a 65% chance the event will happen.

For example:

On Kalshi, traders can buy contracts like “Will U.S. CPI inflation exceed 3.0% this month?”, settled against official government data.

On Polymarket, traders might speculate on “Will Donald Trump win the 2024 U.S. presidential election?” or “Will the SEC approve a spot Bitcoin ETF this quarter?”

In both cases, the price aggregates beliefs but the context and incentives differ sharply.

The Case for Prediction Markets as Forecasting Tools

1. They Often Beat Polls and Experts

Prediction markets have repeatedly shown strong forecasting performance, especially in elections and macroeconomic outcomes. Unlike polls, participants risk real money, which discourages expressive or partisan answers.

For instance:

Polymarket’s odds on U.S. elections have often shifted faster, and more accurately, than traditional polling averages following debates, indictments, or economic releases.

Kalshi’s markets on Fed rate decisions and inflation releases closely track professional forecasters and sometimes anticipate surprises before official announcements.

The structure rewards people who are right and penalizes those who are wrong.

2. They Aggregate Dispersed Information

Markets are effective at pooling information from people with very different knowledge bases.

A single Kalshi contract on “Will the Fed raise rates at the next FOMC meeting?” may incorporate:

Economists modeling inflation

Traders watching bond markets

Business owners reacting to credit conditions

Similarly, Polymarket’s geopolitical markets, such as “Will a ceasefire be signed this year?”, blend insights from journalists, regional experts, and informed observers worldwide.

3. They Provide Real-Time Signals

Unlike polls, prediction markets update continuously.

When news breaks, prices adjust within minutes. This makes them attractive to:

Investors

Risk managers

Journalists

Policymakers seeking probabilistic signals rather than binary headlines

The Case for “This Is Just Gambling”

Despite their forecasting strengths, critics argue prediction markets are fundamentally betting platforms and sometimes they’re right.

1. The Mechanics Look Like Gambling

Binary outcomes, zero-sum payouts, and emotional participation (especially in sports, celebrity, or election markets) make prediction markets feel indistinguishable from sportsbooks.

On Polymarket, contracts like “Who will win Best Picture at the Oscars?” or “Will Taylor Swift announce a new album this year?” clearly blur the line between forecasting and entertainment.

2. Manipulation and Insider Trading Risks

Thin or lightly regulated markets can be distorted:

Wealthy traders can temporarily push prices to shape narratives.

Participants with non-public information may profit unfairly.

These concerns are why Kalshi imposes position limits, restricts certain political markets, and ties settlement strictly to objective data while Polymarket, with fewer guardrails, moves faster but accepts greater risk.

3. Ethical and Political Objections

Betting on elections, wars, or disasters makes many people uncomfortable. Critics argue that markets predicting government shutdowns, wars, or natural disasters commodify civic life and human suffering, even if the forecasts themselves are accurate.

Kalshi vs. Polymarket: Two Philosophies

| Feature | Kalshi | Polymarket |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation | U.S. CFTC | Offshore / crypto |

| Example markets | Inflation, Fed rates, weather | Elections, crypto, geopolitics |

| Market approval | Slow, formal | Rapid, reactive |

| Political betting | Limited | Extensive |

| Position limits | Yes | No |

| Legal clarity (U.S.) | High | Low |

Kalshi emphasizes legitimacy, compliance, and hedging, while Polymarket prioritizes speed, liquidity, and global participation.

Can Prediction Markets Replace Insurance?

Robinhood’s CEO has suggested prediction markets could act as a cheaper hedge against disasters. In limited cases, such as businesses hedging regulatory outcomes or weather-related risks, this idea has merit.

For example:

A utility company might hedge heatwave risk using a Kalshi temperature contract.

A crypto firm might hedge regulatory risk using a Polymarket ETF-approval market.

But prediction markets lack the guaranteed payouts, customization, and loss-matching of traditional insurance. At best, they complement, not replace, insurance.

So What Are They, Really?

The most accurate framing is this:

Prediction markets are forecasting tools built on gambling mechanics.

They are not random games of chance but neither are they neutral scientific instruments. Their accuracy depends on liquidity, incentives, participant quality, and rules.

When used thoughtfully, they can outperform polls and expert consensus. When used casually, they function like speculative betting.

Bottom Line

Prediction markets are powerful, imperfect tools for collective intelligence. Platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket demonstrate that the same core mechanism can serve very different purposes depending on regulation and intent.

The real danger is mistaking probabilities for certainties, or entertainment for insight.